Results of the BAJ Study «Situation and Needs of Belarusian Media Representatives»

The study shows that in addition to political pressure from professional activities, media workers are also affected by other factors, such as lack of adequate access to health care or struggles with finding sustainable employment.

Image: BAJ

The BAJ’s primary objective is to protect and empower journalists. The individuals behind the editorial offices and positions are human beings with intertwined personal and professional challenges. This report presents the findings of the third iteration of the study «The State and Needs of the Belarusian Media Representatives,» conducted by the Belarusian Association of Journalists. Last time the BAJ conducted a similar survey in 2021.

Who participated in the study?

The study is based on the data collected from an anonymous survey of 211 participants and the findings from ten in-depth interviews.

The quantitative survey was completed by a sample of respondents aged 25–55, comprising approximately an equal number of men and women. Of these, 80% are employed in the media sector. 10% are currently unemployed due to a lack of job opportunities, while 4% have opted to pursue alternative career paths. Another 2% cannot work due to the political situation in the Republic of Belarus. Less than 1% are not working because they are studying or retired.

The in-depth interviewees were mostly women (7 out of 10). The respondents’ age groups are 23–27, 30–42, and 47–62.

Most respondents have extensive experience working across various positions and media. Several people are representatives of nonprofit organizations. Most of the respondents have worked in regional and district-level state-sponsored media and independent media at different stages of their careers. Two participants started their careers relatively recently—after 2020.

Interview participants were recruited using convenience sampling. This means that those professionals who responded to the survey and agreed to do an in-depth interview were invited to participate in the study.

Key findings. Journalists are in crisis, and not just professionally

The survey shows that journalists are experiencing an acute professional and existential crisis. The interviews allowed us to highlight how different groups of professionals are experiencing the realities of the crisis, depending on their profile and professional experience, current place of residence, age, and gender.

This is due not only to politically motivated repression and occupational hazards, forced displacement, and the loss of the opportunity to be close to loved ones and former colleagues but also, in many cases, the lack of stable employment and access to health care.

Professional problems

Belarusian non-state media are experiencing a financial crisis that makes it difficult to find employment. People who do find it tend to have a hard time making ends meet on a journalist’s salary, according to respondents.

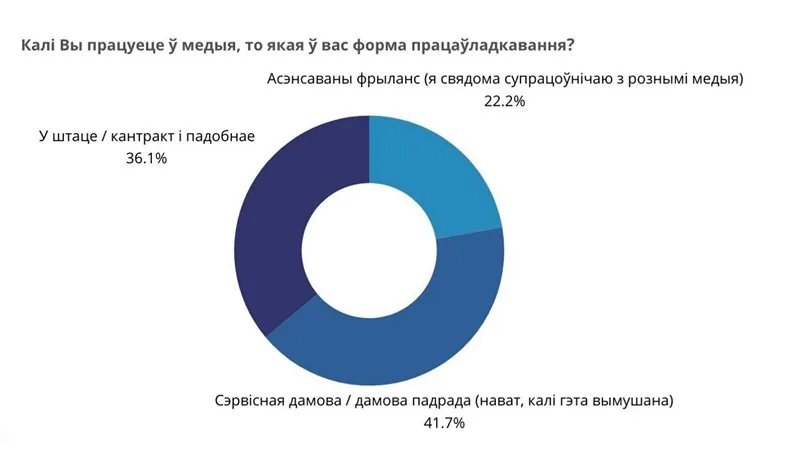

In addition, some editorial offices may delay paying salaries and fees due to a lack of funds. The quantitative survey showed that only 36.7% of respondents have a full-time employment contract.

Most colleagues have service contracts/independent contractor agreements or work freelance. In in-depth interviews, the majority of informants indicated that they engage in work across multiple media or projects. Some also reported holding part-time positions in other fields. Furthermore, coordinating multiple projects and types of work in emigration is a more complex undertaking, as it involves additional challenges related to the regularisation of stay and integration.

Results of the BAJ Study «The Situation and Needs of Belarusian Media Representatives» December 5, 2024

Those interviewed noted with acute anxiety and a sense of injustice that many of their colleagues, both in Belarus and abroad, are leaving the profession. The combination of persecution, risks of repression, a funding crisis, and a critical level of uncertainty about the future in emigration may result in a narrowing of the Belarusian media space. Many participants indicated they could not envisage a future within the profession or in exile in general due to the prevailing climate of repression, financial constraints, and difficulties encountered when obtaining a residence permit.

There is burnout, overwork, and stress because of the fear that the police will come again and the fear of any visitors (M, 50, more than 15 years in journalism, Belarus).

There’s much uncertainty in the media sector right now. We’re not sure what will happen tomorrow or next year or if we’ll be able to keep working the way we have been. […] Funding is also up in the air. One of the projects that I continue to work on, despite everything, did not receive funding. Everything was fine for 20 years before that (M, 31, 13 years in journalism, 3 years in forced emigration in Poland).

Results of the BAJ Study «The Situation and Needs of Belarusian Media Representatives» December 5, 2024

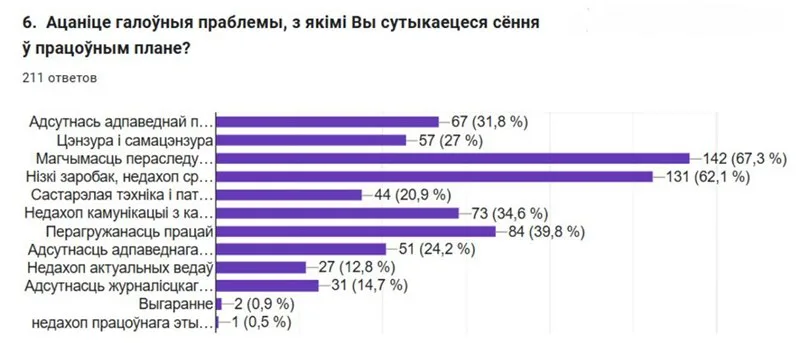

- The risk of persecution for me or my family due to my professional work: 67.3%.

- Low wages and unstable funding for media outlets: 62%.

- Excessive workload: 40%.

- Limited communication with colleagues: 34%.

- Difficulty finding suitable job opportunities: 32%.

- Issues with censorship and self-censorship: 27%.

- Lack of appropriate workspace: 24%.

- Outdated equipment in need of replacement: 20%.

- Absence of a local journalistic community: 14%.

The dearth of stable employment opportunities on a contract basis renders journalists vulnerable and socially unprotected. The fast-paced nature of work, financial and social pressures, and an overall lack of stability impede the timely attention that should be given to health issues, which are a significant concern for many individuals.

Almost everyone works as an individual contractor, so legally, people are not entitled to vacation or sick leave. You run a fever, but you sit and work. People try to accommodate, find a compromise or a substitute, or postpone, but it depends on interpersonal relationships. And unfortunately, there are no protections (F, 27, working in the media since 2021, double emigration—Lithuania and Poland).

Results of the BAJ Study «The Situation and Needs of Belarusian Media Representatives» December 5, 2024

- Residency challenges: 19%.

- Difficulties obtaining residence permits for family members: 14%.

- Discrimination based on Belarusian citizenship: 15%.

- Physical health problems: 35%.

- Mental health struggles: 49%.

- Lack of health insurance: 28%.

- Feeling isolated due to the absence of friends and loved ones in the new country: 26%.

- Language barriers in the host country: 40%.

- Challenges finding educational institutions for children: 3%.

- Lack of childcare support for young children: 10%.

Figures are rounded to the nearest whole number.

Results of the BAJ Study «The Situation and Needs of Belarusian Media Representatives» December 5, 2024

Even for those who work in-house, the issue of health insurance and its payment remains relevant. In many instances where emergency surgery or other urgent medical care is required, the only available option is to pay for medical services, as there is no time to wait for more affordable or free alternatives. The vast majority of participants indicated that they frequently need a clearer understanding of the system and the process for getting a doctor’s appointment in their host country, even when they have individual or family insurance.

Several respondents indicated that they cannot afford health insurance and are unsure how to address this issue. In many cases, the only viable options are diaspora assistance (a loan from friends and acquaintances or a crowdfunding campaign), individual grants, and opportunities to improve health provided by professional journalistic organizations such as the BAJ (short-term vacation or covering therapy or surgery expenses).

Age

Age is an additional factor impacting quality of life and access to the labor market. Individuals with considerable professional experience but of an advanced age are particularly vulnerable among journalists in exile.

While younger professionals can often find alternative roles, such as social media management and vlogging, that do not require extensive experience, those with more traditional backgrounds can face challenges when seeking employment. One older respondent indicated that he had applied for several positions in the media and related fields but could not secure in-house employment due to his age. His experience illustrates the challenges Belarusian journalists face in forced emigration.

I’ve never gone through a life crisis like this one, so it’s been pretty tough. My life was no bowl of cherries, but it was manageable [laughs]. But things get tricky when there’s no money, illnesses strike, and no one employs you in City X because you are over 60. When you’re in a bind and don’t know if you’ll be able to pay the rent tomorrow, you don’t have the funds, and X media hasn’t paid the agreed-upon minimum wage for five months. Not only to me but to several dozen people (M, 60+, has worked in the media since the 90s, 3 years in forced emigration to Poland).

Female journalists recently entering the profession also cite a lack of opportunities to develop professional contacts as a challenge. This is due to the geographical fragmentation of professional communities (Poland, Georgia, Lithuania) and limited access to established networks of contacts, which are more readily available to journalists with long-standing experience. In addition, professionals of all ages have indicated that the secrecy of communication channels and professional relationships is a significant challenge in the current job market, as evidenced by the quotes below.

So, the vacancies are circulated in the community or journalist chats, but the employer already has some people in mind who they would like to see in this vacancy (F, 35, 8 years in the media sphere, 3 years in forced emigration in Poland).

There are not many jobs posted publicly. From what I’ve seen, a lot of people get jobs, if not through acquaintances—it would be wrong to say this because these people have specific skills—then by having access to job postings in general (F, 27, working in the media since 2021, double emigration—Lithuania and Poland).

The geographical fragmentation of professional communities also affects everyday work communication. For example, a large diaspora and a dedicated media hub in Warsaw contribute to professional support. The media hub has become a great place to work and socialize, but some respondents say there used to be more interesting events there.

Journalists based in Vilnius, Warsaw, and Bialystok report having a robust network of contacts within reach. In contrast, journalists from Wrocław and Tbilisi cite a lack of offline communication and a sense of isolation. This issue is especially relevant for those who work from home.

I talk with my colleagues once a week (at staff meetings), and the rest of the time, we text each other. I feel the lack of verbal communication is significant. And not only with colleagues. There’s a real lack of communication (F, 47, more than 10 years in journalism, 2 years in forced emigration in Poland).

Since so many teams and publications are spread across different cities and countries, there are few team-building opportunities (M, 31, 13 years in journalism, 3 years in forced emigration to Poland).

Not being able to stay in touch with colleagues all the time. It’s happening online, but it’s less intense than it was in Belarus. This is online communication. Firstly, we are in different cities. Secondly, how we work means my colleagues don’t usually spend eight hours in the office.

In most cases, it’s a rented apartment without furnishings. The only thing that is arranged is a sloppy-built studio (F, 35, 8 years in the media sphere, 3 years in forced emigration to Poland).

Interview participants address equipment and premises issues in different ways. In three out of ten interviews, respondents indicated that they had the opportunity to upgrade equipment (computers) at the expense of the editorial office. In other instances, journalists utilize either office equipment, frequently requiring replacement, or personal equipment purchased with their funds. Furthermore, no concerns were raised regarding the suitability of the office space in any of the interviews, as many employees have become accustomed to working from home or in co-working spaces.

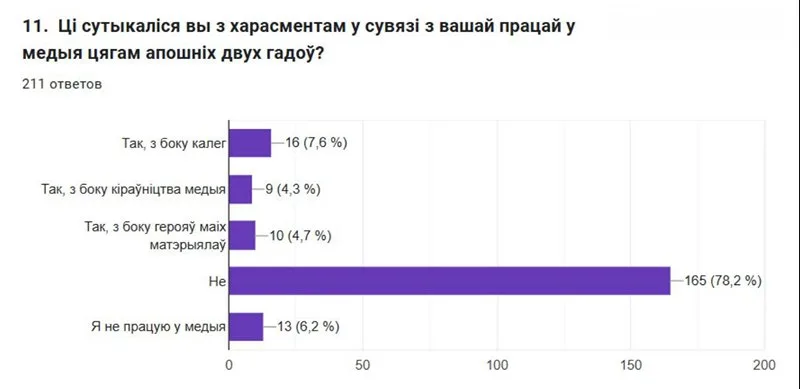

Harassment

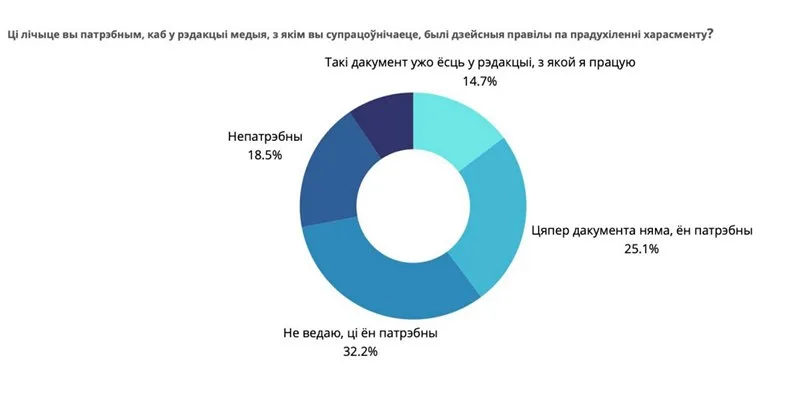

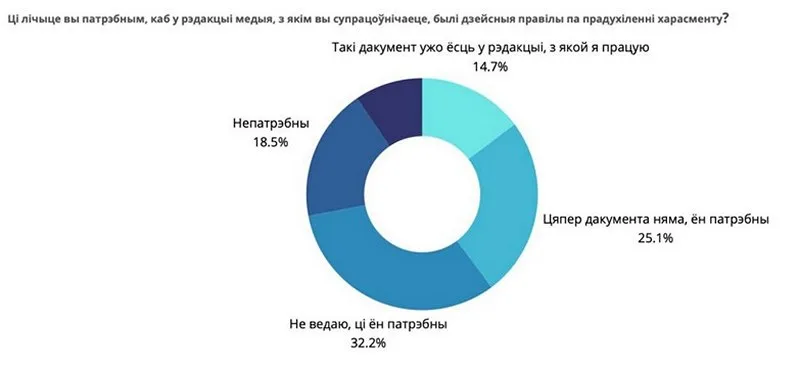

16% of respondents indicated they had experienced harassment, representing 34 individuals out of 211. It is noteworthy that the responses did not vary significantly based on gender. Both women and men reported experiencing harassment at a similar rate.

Results of the BAJ Study «The Situation and Needs of Belarusian Media Representatives» December 5, 2024

Some respondents highlight the challenges of communicating with colleagues in a public setting, the occasionally toxic environment in professional online communities, and misunderstandings in editorial offices. They also cite difficulties in fostering professional solidarity.

Emigration has brought some tricky communication issues to the fore. I’ve noticed that journalistic chats can sometimes get heated, with debates breaking out on various topics, from language to headlines to ethical issues. I sometimes wonder if it’s worth asking colleagues for help. You might get some advice or get hit in the head (F, 35, 8 years in the media sphere, 3 years in forced emigration to Poland).

We often have trouble giving each other constructive criticism. When something comes up that needs to be addressed, instead of starting a discussion, people tend to launch attacks. Once again, it seems like a flamewar without any constructive dialogue, decision-making, or reaching a consensus (F, 27, working in media since 2021, double emigration—Lithuania and Poland).

The communication that we used to have in Belarus is no longer there. There are no community events. The things that exist do not bring satisfaction. I want to stay away from everybody (F, 38, 13 years in journalism, 3 years in forced emigration to Poland).

Cases of violating work communication ethics and psychological abuse were reported. These included colleagues speaking in an unacceptable tone of voice and using foul language in public discussions.

Harassment was not sufficiently addressed in in-depth interviews. More sensitive methods are needed to build trust when talking about this topic (including mediation or conversation circles). Quantitative interviews show that harassment should be discussed regardless of the respondent’s gender.

I had a male colleague who humiliated all the women who worked with him. He didn’t offend me—there was no harassment—but he’s the person who makes you feel dumb working with him. You shouldn’t feel that way at work. There was a situation when he cussed me out. It took me three days to come to my senses. I am a vulnerable person. It made me feel terrible; I lost my ability to work. […] It wasn’t even a mistake on my part. The person just lost his nerve. […] The same person could call me at 3 a.m. and discuss work. This is unacceptable (F, 27, working in the media since 2021, double emigration—Lithuania and Poland).

Results of the BAJ Study «The Situation and Needs of Belarusian Media Representatives» December 5, 2024

In addition to the professional communication challenges mentioned above, respondents reported declining professional work standards due to a lack of time and human resources for fact-checking and working on specific topics (e.g., with vulnerable groups).

There are fewer and fewer journalistic genres out there, and people are trying to do too many things at once. There’s a lot of talk about the challenges of using constantly changing terminology. The spread of hate speech is worrying. Many have had to deal with modern challenges in the profession, such as the competition for an audience (clickbait, reducing time for proofreading, etc.).

If you have competition or colleagues who will point out mistakes, it’s easier to maintain a professional level. But when everyone is chasing clicks, when there are 4–5 major Belarusian media outlets in exile, and they all work approximately the same way, striving to attract as many readers or viewers as possible, then the level of journalism drops. […] We don’t have a clear idea of what constitutes acceptable levels of clickbait. Especially if the headline doesn’t contain a direct insult but is close to it (F, 35, 8 years in media, 3 years in forced emigration in Poland).

At the moment, I am working on an initiative that covers Belarusian society’s attitude towards LGBTQ+ people. But we have noticed recently that coverage of such issues has been diminishing in the media space. […] Many editorial offices work expressly with a political slant and have started to write less about vulnerable groups (F, 33, 9 years in the media sphere, forced emigration to Georgia).

Even the approach to wording is changing. We used to write «migrants and refugees,» but now human rights activists say we should write «migrants, including refugees.» Words and approaches change, but the media might not be able to keep up with it all because of time constraints (F, 33, 9 years in the media sphere, forced emigration to Georgia).

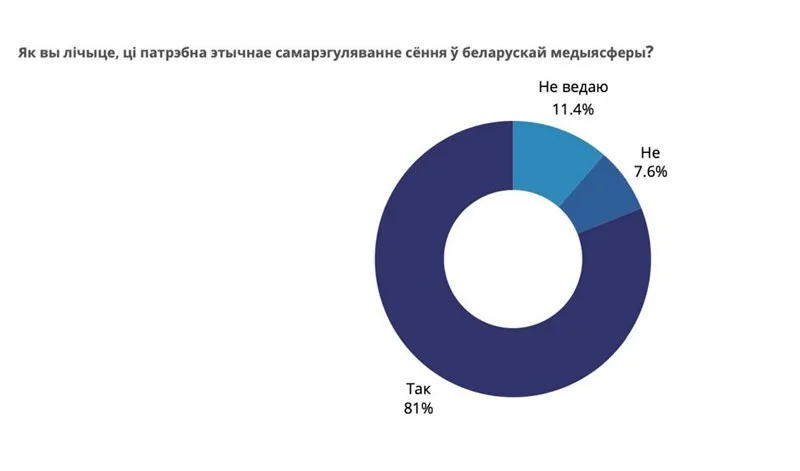

In this regard, participants raise issues of professional and ethical standards for journalists and the need to update the current professional code. Many respondents believe that establishing written rules and fostering constructive public dialogue within the professional community can assist journalists in navigating ethical challenges in publishing materials, resolving conflicts, and addressing violations of professional ethics in their daily interactions with colleagues.

Results of the BAJ Study «The Situation and Needs of Belarusian Media Representatives» December 5, 2024

The respondents indicated that ethical self-regulation offers insight and resources for «navigating various conflicts and understanding the boundaries of acceptable conduct for journalists.» It is of the utmost importance that respondents refrain from any action that could harm their sources in Belarus or promote the agenda of the repressive regime.

Respondents to our in-depth interviews highlighted that they work in media organizations and NGOs with written ethical guidelines. The BAJ code of ethics also guides them. However, in each particular case, the existing regulations may prove insufficient. The issues and new challenges outlined above necessitate a review and potential updates to the code.

Results of the BAJ Study «The Situation and Needs of Belarusian Media Representatives» December 5, 2024

Without written rules in their editorial offices and organizations, survey participants resolve controversial issues with colleagues in discussions on staff meetings and «editorial disputes.» Several respondents indicated that their work teams are implementing written ethical self-regulation rules.

In some interviews, the necessity for professional associations to facilitate the creation of infrastructure opportunities for journalists to unite and reinstate the practice of self-assessment and self-regulation, which was previously established in Belarus, was discussed. This included the formation of a specialized ethics committee and the ongoing work of «Journalists for Tolerance.»

Censorship and self-censorship—persecution for the profession

All respondents’ primary challenge is to achieve an optimal balance between the quality of media materials and the security measures necessary to protect sources of information, journalists themselves, and their families and colleagues in challenging circumstances. All respondents confirmed that, as a result, censorship and self-censorship are practiced daily within the teams.

The individuals responsible for creating the materials must consider even the most fundamental risks; editors and managers are also tasked with this responsibility. This is most relevant for professionals based in Belarus. A journalist from Belarus noted that working in such conditions and producing materials is becoming increasingly difficult. It should be noted that media professionals working abroad may be exposed to certain risks, as many of them have relatives or property in Belarus.

The interviews revealed instances where, as a result of the professional activities of journalists abroad, their relatives in Belarus were subjected to interrogations or had their property searched and sequestered.

Training

Most participants in the in-depth interviews utilized available resources and professional learning projects. They indicated that should one desire it, there are always opportunities to expand knowledge and competencies. Some interviewees did, however, highlight the issue of media stagnation. They indicated a focus on established practices and speakers. Furthermore, they highlighted the necessity of modernizing work tools and training content.

The issue is that some media outlets are stuck in their ways. I don’t mean in 2020, but rather in terms of the tech and methods used to build a brand (M, 31, 13 years in journalism, 3 years in forced emigration in Poland).

I’m having trouble putting it into words, but I often feel like I’m going through the motions and not progressing much. It’s a lack of knowledge and training and an overall feeling of stagnation (F, 38, 13 years in journalism, 3 years in forced emigration in Poland).

Among the most pressing training needs identified were improving skills and expanding the availability of artificial intelligence tools. Media professionals note that the skills discussed in training sessions, including those with foreign speakers, are not always applicable to the work process. The problem is that the available AI tools are limited in language versions and functionality.

Another request of the older generation of journalists, among others in Belarus, is training on social media platforms such as TikTok. One of the journalists noted that it is sometimes difficult for him to quickly and efficiently create content on TikTok, select images, and publish posts to the platform.

Many exiled media professionals noted that more opportunities should be created for networking and sharing experiences between different projects. They would like to discuss the relevant terminology (language for reporting on vulnerable groups, feminism, etc.) and the profession’s modern challenges.

Mental health issues

Special attention should be paid to emotional burnout and media professionals’ mental health. Each respondent has a unique experience that, in some way, relates to mental health challenges that have arisen in the context of a professional, social, or personal crisis. Two out of ten interviews revealed that respondents had attempted suicide, and two additional media professionals had been diagnosed with depression. In one interview, the female respondent discussed the issue of domestic violence and the challenging process of mental recovery.

All ten interviewees sought counsel from psychotherapists. Some have borne the cost of their sessions out of pocket, while others have accessed pro bono services available in the community. All interviews included a request for long-term access to therapists and mental health medications. It is often challenging to find a specialist who provides practical help within short-term free programs («It would be great to have the chance to use these services on an ongoing basis, rather than just ten sessions every six months or so.»)

Furthermore, short-term retreats and opportunities to relax, including short-term vacation programs available in the professional community, can improve psychological well-being.

The main personal issue I have with work is that my health is suffering due to stress. Therefore, a good rest is very valuable. This summer, a project paid for me to stay at a health resort, which was a great experience. Wouldn’t it be great if we could take a vacation like this every year? Just knowing it’s possible makes a big difference (M, 50, over 15 years in journalism, Belarus).

I don’t think pro bono therapists are particularly eager to help. My first therapist gave me a lecture, didn’t listen to what I was saying, and was repeating himself (F, 47, over 10 years in journalism, 2 years in forced emigration in Poland).

As identified by interview participants, another crucial area of requested assistance is providing individual guidance and support in locating specialist care for individuals facing crisis situations. This will facilitate more expedient access to targeted care by eliminating the need for the traumatized person to search for a specialist and schedule multiple appointments.

Residency issues, language barrier, and discrimination in the host country

Journalists in exile face difficulties in regularising their stay. As a result, they cannot obtain timely medical care for themselves and their dependents and access to educational opportunities for their children.

The granting of international protection plays a role in addressing residency issues. However, the legal status of these individuals can change depending on the political situation in the host country, creating uncertainty about future regulatory change.

As a result, some respondents have a double experience of emigration (from Lithuania to Poland). Some plan to change their country of residence because they feel politically endangered (particularly, in Georgia).

Results of the BAJ Study «The Situation and Needs of Belarusian Media Representatives» December 5, 2024

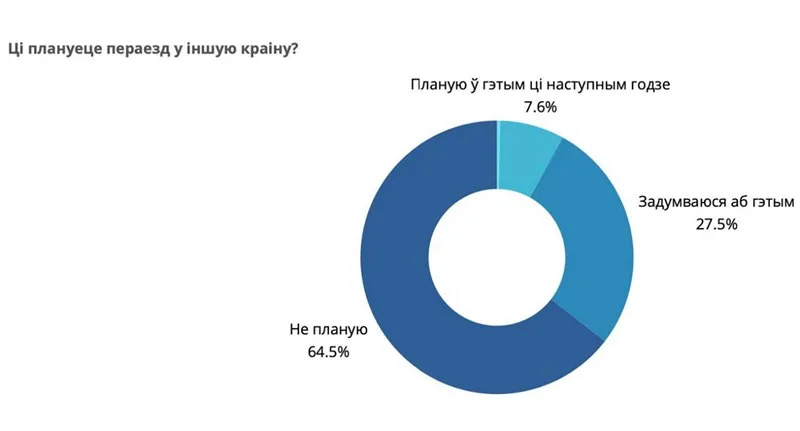

A relatively large percentage of colleagues are still concerned about the possibility of changing their country of residence. For example, 27.5% of respondents are considering moving, and another 7.6% plan to move this year or next. Most respondents who chose this answer indicated living in Belarus, Lithuania, or Georgia.

64.5% of respondents said they did not plan to move to a new country. Interestingly, responses to the question were virtually unaffected by journalists’ age and gender.

An expired passport, which can no longer be renewed outside Belarus, complicates the situation in many cases. Due to the aforementioned factors and the inability to obtain educational certificates from Belarus, the respondents’ older children cannot commence higher education.

Caring for children from young age to adolescence is an additional factor contributing to women’s overall experience in this field. Female journalists have noted that due to human insecurity and low wages, parents cannot afford to pay rent and necessary medical care for their children. Due to an excess of work and language barriers, it is challenging to navigate the search for an educational institution and communicate with the administration and faculty.

Female respondents indicate that nonprofit organizations and professional communities could assist in addressing these issues by providing accessible and understandable guidance that concisely outlines the necessary steps. They also need direction to resources that facilitate searching and communication with educational institutions.

For female journalists considering starting a family, the question of financial security for their future family is a significant concern, particularly in light of the challenges associated with forced emigration. A considerable challenge for female journalists in Poland is the lack of access to contraceptives and the limited availability of abortion services.

A significant number of respondents highlighted the challenges associated with learning the host country’s language. They experienced discrimination due to language barriers in medical or educational institutions. Due to excessive work and the challenging nature of specific languages (in particular, Lithuanian), confident communication with native speakers is an issue.

This can significantly impact job search opportunities. However, many media professionals noted that they are trying to learn the language on their own or with the help of free and paid courses. Some respondents note that the availability of offline courses with live practice can significantly speed up the language learning process and help overcome the barriers described above.

This is not easy. While looking for work for several months, I kept coming up against the same issue. For example, my Polish wasn’t good enough to get me hired as a security guard (M, 60+, has been working in the media since the 90s, 3 years in forced emigration in Poland)

I didn’t start learning Polish until later in life because I was worried about losing my Belarusian identity. […] In the first month of my time in Poland, I had to speak with the school principal. I spoke slowly in Belarusian—we understood each other. It seemed to me that he was open to it. Then, there was a pretty scary incident when an ambulance was called to my daughter’s school because she was having heart pain. After that, we went to a private pediatric cardiologist. I paid a lot of money. The doctor started to explain something in Polish. I asked him to speak more slowly because I was still learning Polish. (I had memorized this phrase in Polish before the visit). The doctor threw up his hands, said something like, «No talking, no counseling,» and shooed us out the door. (F, 47, over 10 years in journalism, 2 years in forced emigration in Poland)

I can now order something in Georgian. When asked for directions, I can reply where to go, which is useful in small daily situations. I have some acquaintances among Georgians. I can text them in Georgian. I don’t know everything, but I can grasp some basic concepts. I’m following a few Georgian bloggers, so I’m getting a feel for the language there (F, 33, 9 years in the media sphere, forced emigration to Georgia).

As evidenced by both quantitative and qualitative research, the Belarusian media sphere is experiencing a period of crisis. It requires infrastructure changes, new approaches, and resources to unite professional communities and technological and financial support.

Media professionals make collective and individual efforts to uphold professional values and constructive dialogue. However, the situation is compounded by the acute challenges of repression and the associated risks, mistrust, and lack of resources within the community, as well as the technological and ethical challenges of the modern media industry.

The most urgent concerns that directly impact respondents’ work are legal and social insecurity, work overload, and the narrowing of opportunities to change jobs or work in different genres and areas. Furthermore, there are additional challenges related to the residency and discrimination faced by professionals seeking to emigrate, as well as the potential for burnout and the impact on physical and mental health.

Brief findings:

- The situation of Belarusian journalists is precarious, both within Belarus and in the context of forced emigration.

- The Belarusian media sector still requires substantial international and domestic support to ensure its continued ability to develop and retain its human capital. The work of Belarusian support organizations and international partners is essential to this effort.

- It is crucial to address the following issues: the decline in media job opportunities, the challenge of registering media personnel as employees, and the lack of social protection for media professionals. Targeted psychological and medical assistance programs are needed.

- There is a continued need for local language learning programs in host countries.

- Although harassment of media workers is not the primary issue, there is still a need to develop policy documents and create mechanisms to protect them.

- The situation for journalists remaining in Belarus is particularly challenging.

@bajmedia

@bajmedia